Old World Techniques are New Again

By Karen B. Wolf

A reaction to technology, the appreciation of craftsmanship, and historical art processes are being rediscovered by local craftsman and large manufacturers embracing long old world techniques and reinventing with a new twist. The movement seeks to create one of a kind, nonhomogenized artful pieces that tell a story around the technique being used. The “New Traditionalist” and among the millennial set, “Grand Millennial” as well as the “Maker” lifestyle trends have embraced this upswing of guild based artisan techniques and propelled this revival into the mainstream.

In 2018 the first major cultural exhibition dedicated to European Craftsmanship was created, the Homo Faber event. “Homo Faber is an expression that was first coined during The Renaissance and it captures and celebrates the infinite creativity of human beings,” Johann Rupert, Co-founder of the Michelangelo Foundation, says. “The exhibit will provide a panoramic view of European fine craftsmanship but it will nevertheless have a singular undercurrent: what human beings can do better than machines.”

Just a few of the techniques I am seeing emerge as reinvented are:

Marquetry: Marquetry is a decorative technique usually applied on furniture, smaller wooden objects and pictorial panels. To embellish an object or create a work of art on a panel, the marquetry maker chooses several different woods in a wide variety of colors, which he cuts, assembles and applies according to his inspiration and the motifs he desires to create. Bethan Laura Wood in London uses marquetry as part of her “super fake” collection where she creates laminate-marquetry tables and carpets to look like geodes and terrazzo.

Bethan Laura Wood Hot Rock Cabinets

Atelier Lison DeCaunes Straw Marquetry

Smash Flooring

In flooring we are seeing marquetry woodwork in re-interpeted graphic designs

Cristina Celestino Viennese Straw marquetry

Simon Orrell Designs Straw Marquetry

Grisaille: Grisaille is a painting technique by which an image is executed entirely in shades of gray and usually severely modeled to create the illusion of sculpture, especially relief. … In French, grisaille has also come to mean any painting technique in which translucent oil colours are laid over a monotone underpainting. Grisaille originated from the French word “gris” which means “gray”. The first known use was in 1848. I am seeing this technique emerging in fresh new ways and in its original format.

De Gournay grisaille paper in powder room by Frank Ponterio

Susan Harter Hand Painted Mural

Novolette Wallpaper Cole & Sons

Florence Girette Wallpaper (Veranda Image)

Historical Pigment Paint: In the 18th and early-19th centuries, before the advent of pre-mixed paints in the 1870s, interior house paint was generally mixed on-site and in small batches. These paints generally had short shelf lives and were made as they were needed.

Paints could be sorted into two primary categories: oil and distemper. The main difference was the binder used to suspend the pigment in paint. For oils, the binder was linseed oil. In distemper, pigment was mixed with hide glue and water.

What these different paints had in common was the presence of colored pigment. These pigments generally came from organic sources like the iron oxides of ochre and sienna to yield colors like yellow ochre and burnt sienna. The pigments were ground using a muller and slab.

Paint was highly saturated due to the sheer amount of pigment in the mix. The paints also had a textured finish because of the hand-ground pigments.

Currently, companies and paint lines are popping up specializing in the original pigmentation and colors of historical paint. Guerra Paint & Pigment in NYC specializes in single color historic paint pigments.

The Old-Fashioned Milk Paint Co. carries on this age-old practice with organic paints made from lime, natural pigments, and casein (a protein found in milk). Old-Fashioned Milk Paint is available in 20 colors, or as a base with no pigment for custom-blending.

Ground pigments and a small-batch process lend Olde Century Colors’ paints their authenticity. As the paint dries, subtle brushstrokes remain visible in the film, a hallmark of traditional paint produced in handcrafted batches in the 19th century. Fourteen of Olde Century’s 36 colors, including Tinderbox Brown and Goldenrod Yellow, are designated for Bungalow, Craftsman, and Prairie-style homes.

The Real Milk Paint Co. offers a powdered milk paint formula consisting of lime, pigment, and purified casein—just add water, and you’re ready to paint. Colors are available in traditional and historic blends, or you can achieve your desired shade by adding varying amounts of white pigment.

And Pedro Da Costa Feigueiras of Lacquer Studios crafts small batch paints for his commissioned projects.

Guerra Paint and Pigment Store

Real Milk Paint Pigments

Century Paint Benjamin Moore

Olde Century Colors Paint

Cire Perdue: A lost wax metal casting process where molten metal is poured into a mold that was created by a wax model. Once the mold is made the wax model is melted and drained. Cire Perdue was used about 4,000 years ago by the Egyptians, Greeks, Africans, and Masters of the Italian Renaissance to cast superbly detailed bronze sculptures. Although the process has been improved today through modern tools it remains time-consuming, requiring many hours of effort by skilled artisans. I have been noticing the use of this process in the bespoke luxury market.

Maison Integre – Ade

Osanna Visconti’s bespoke candlesticks are a beautiful example of the process.

Luna Paiva Bronze Artist

Embroidery | Needlepoint: While this art form may sound more common, it is quite complex utilizing techniques like crewel work, berlin woolwork, art needlepoint and the widely known cross-stitch. In 2020 the Homo Faber Exhibition will actually be holding a featured workshop led by Maison Lesage, an embroidery atelier founded in 1858, by Albert and Marie-Louise, who sought to be a custodian of old-world embroidery techniques. Today, embroidery craft classes are popping up all over the nation and embroidered passamentrie, art and home products are hugely popular. The Grand Millenial Generation has a huge penchant for this art technique in its pure form and with a modern twist.

Embroidery Kit Sunday Mornings

Sara K Benning Embroidery Artist

Sara Long Artist

Needlepoint on Furniture

Dragon Point Needlework

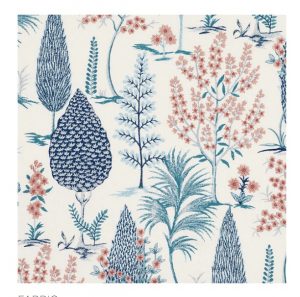

Dorset Collection Old World Weavers, Scalamandre.

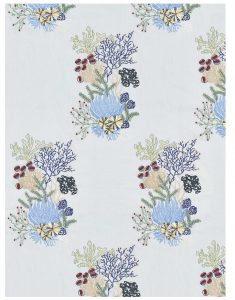

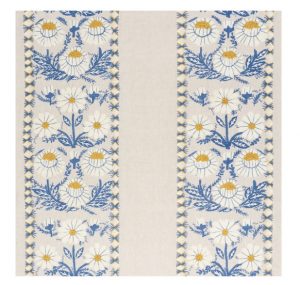

Schumacher Marguerite Embroidery (newly released as a popular archival fabric)

Pandora Embroidery Schumacher

Embroidered Bedding Anthropologie

Filigree: The art of Filigree was born during the Roman period and it was passed down through generations of skilled medieval jewelers, often emulating the work of the Byzantine goldsmiths of Constantinople, embellished crosses, reliquaries and the covers of Bibles. It is one of the most beautiful forms of metalworking where skilled artisans solder tiny beads and twisted threads to create an intricate lace-like pattern. Boca do Lobo is a bespoke guildery that creates artisan-inspired pieces celebrating age-old techniques. Their filigree mirror by Rui Pinto from Portugal is absolutely exquisite.

Boca DoLobo Filigree Mirror

Emtek Hardware in the Filigree Style

Filigree Table Caracole

1930’s vintage sconces Chairish

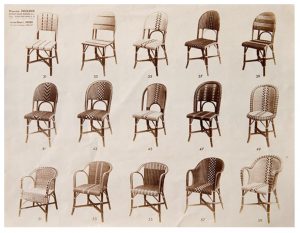

Rattan Weaving: Probably one of the most recognized old-world traditions wicker refers to a technique of weaving fibers using natural rattan, the stem of a sturdy yet flexible climbing palm. The rattan creates the structure of the piece, and thin strands from the interior of the stem are used to weave on the rattan base. This combination is called wicker. The last of the artisans heat stiff poles of rattan into malleable rods that are bent on a metal frame to create works of art. Wicker’s peak was in the mid-1800s, when trade routes from Asia brought a steady supply of rattan to Europe. But, the art of weaving from natural fibers dates as far back as ancient Egypt.

Today, we are now seeing an elevated approach to the art by a few ateliers including; Ines Lucas and Maison Drucker in Paris, The Bonacina Atelier, Soane Workshop and Larsson Korgmakare.

The Drucker Atelier is one of the oldest and finest Rattan makers in the world. Recently, they aligned with Ines Lucas to create a Deco influenced rattan line that is sophisticated and authentic.

Drucker Atelier

The Bonacina Atelier is a 128-year-old wicker furniture company north of Milan run by the founder’s grandson Mario, along with his wife and children. Bonacina’s grand sloping armchairs and spare, streamlined loungers can be found in Italian hotels like Le Sirenuse, Francis Ford Coppola’s Palazzo Margherita and Villa Feltrinelli.

2014

Soane is a London company committed to creating furniture and fabrics made by craftspeople from across Britain. They purchased the Angraves workshop in Leicestershire the last rattan weaving studio in England and rehired its two chief craftsmen, frame maker Mick Gregory and master weaver Phil Ayres. Their style is very current and artful.

Daisy Lamp

Carasoul Bar Stool

Fern Table

In Stockholm, resides the 114-year-old warehouse of Larsson Korgmakare, the only artisanal rattan workshop left in Sweden. The history and continued success of the business owes much to the acclaimed Swedish designer Josef Frank. In the 1930s Larsson began a partnership with Frank, who is known for his minimal wicker sofas and chairs. The line is still produced today by the granddaughter, Erica for Svenskt Tenn.

Pate Sur Pate: is a French term meaning “paste on paste”. It is a method of decoration in which a relief design is created on an unfired, unglazed body, usually with a coloured body, by applying successive layers of white porcelain with a brush. Once the main shape is built up, it is carved away before the piece is fired. The usual colour scheme is a white relief on a contrasting coloured background. In England was often called Parian ware. The development of pâte-sur-pâte dates back to 1850 in France but the Victorian era was the apex of the technique.

MJ Atelier in NYC, known for its sculptural wallcoverings and authentic approach to the decorative arts, recently employed this relief technique in a ceiling design for Nest Fragrances. Other interpretations in today’s market are widely found in accessories and lighting.

MJ Atelier, Nest Fragrances

Minton Parian Ware Bust (Late 1800’s)

Global Views 2019

Currey and Company Weslyn wall Sconce

Foster Reeve Plaster Millworker